Pascal Was On To Something

Broad sweeping generalizations to explain everything at once are the bane to all good deliberation and advancement, from philosophy to politics to science to well being. But.. my soul craves creating Grand Unified Theorems (GUT) at a biological level akin to the innate need to classify everything we see. So it doesn’t come as a surprise to me that I am searching for underlying perspectives that are – at least through analogy – able to provide understanding to all things of value.

I’ve held on to one such GUT – the Grecian Urn – that I really should capture in words one day. But this past week, I’ve been settling in to a new one that feels pretty cozy, like snuggling under a warm flannel blanket in a Portland winter day. And to understand it, we must begin with Pascal and a famous wager.

Pascal

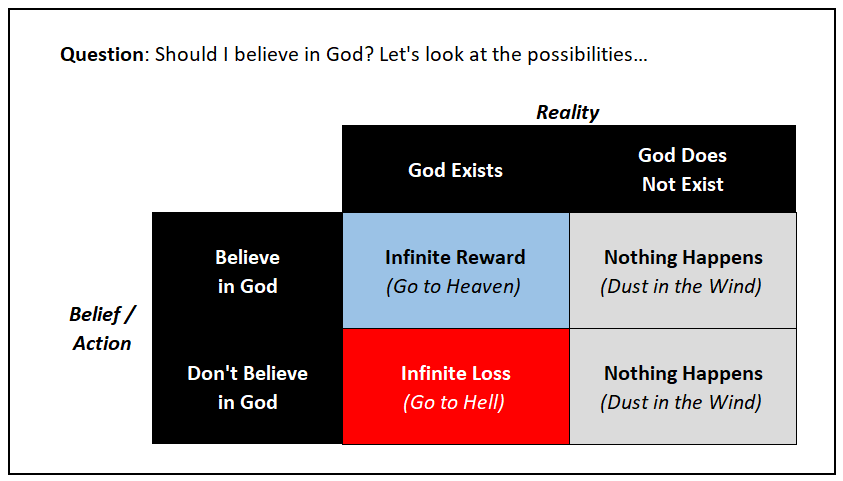

Pascal’s Wager pragmatically confronts the belief in God by drawing a 2×2 matrix to determine the outcomes of different beliefs/realities. Talk about a rational and pragmatic approach to faith!

The point obviously is: given the decision matrix on the belief of God, the cost-benefit analysis in believing in God is highly skewed in favor of believing. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist or minister to figure out which row to choose. So even if we do not believe in God, we must all “endeavor to convince” (Pascal’s words) ourselves in the belief by choosing the second row, because the risk/reward so heavily favors the alternative.

There are lots of ways to counter this line of reasoning, particularly given the hidden flaws in the axis definitions. But methodologically, the approach of building a decision matrix for wagering for fundamental beliefs is a sound approach, methinks.

The subtle point I want to hold on to is how Pascal fundamentally approaches a metaphysical problem as a pragmatic realist. The choice to believe in God based on practical expedients trumps the actual belief and the decision to believe it. Even if he does not believe in God, he still can be practical for expediency sake to choose to “endeavor to convince” himself that God does indeed exist. (Technically he may have been a believer, but his argument is designed at least for those who doubt).

Wagering

I like Pascal’s methodology (assuming you define your axis diligently) because it forces a wager. And wagering is really good.

I’ve been influenced the past two months by the book “Thinking in Bets: Making Smarter Decisions When You Don’t Have All the Facts” by Annie Duke. A famous poker player, Duke argues that wagering is one of the best means to force the brain into rationality. The threat of loss is usually a great counter weight against all of the misleading biases that we have. Honestly, it is one of the few tools we have in our toolkit against a seemingly endless supply of biases that lead us astray.

So I bring this up because it is further validation that mental wagers are an amazing tool to force the brain into rational thought.

So, here’s the end point of the Modicum I had this week: Human Society is built upon successive Pascal’s Wagers made subconsciously. When you look under the covers, this type of wager is pervasive in the societal structure, not just on the topic of religion. I would argue that wagering is exactly what humans have done with metaphysics to allow society to evolve despite the reality of the facts. It is a pervasive process to achieve necessary expedience for a functioning society. OK, that’s my Modicum – but before delving into that extrapolating end point further, let Calvin finally have the stage:

Necessary Expedience

So what if we step back from God and apply the wagering to other locations where, as Duke says, we don’t have all the facts.?

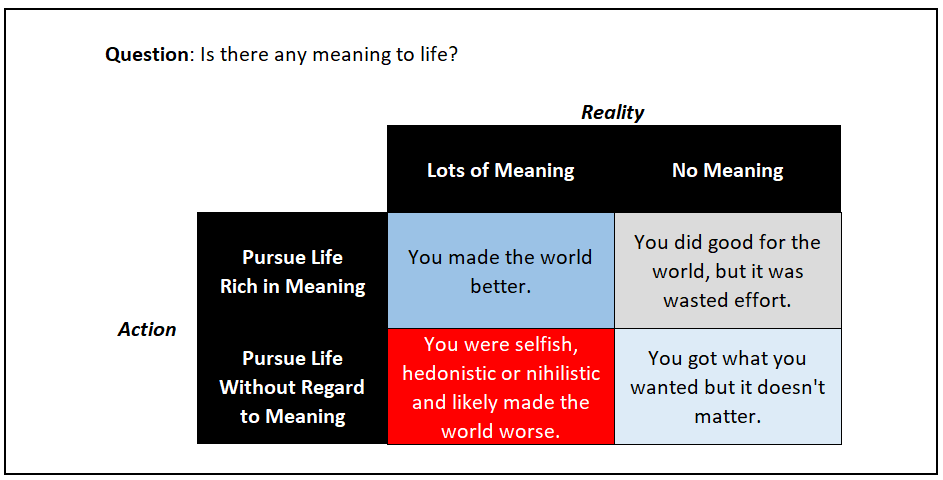

Just one step away from Pascal and God is the common man’s immortal question “What is the meaning of life?” You know that form of the question grates on me, so let’s ask a slightly better version “Is there a meaning to life?”

This says, in Pascal’s thinking, that taking the act of pursuing a life rich in meaning has a higher weighted value than not (although not as strong as Pascal’s example). Makes sense. So like Pascal, we should just go ahead and endeavor to convince ourselves that life truly does have meaning, regardless of whether or not we actually believe it.

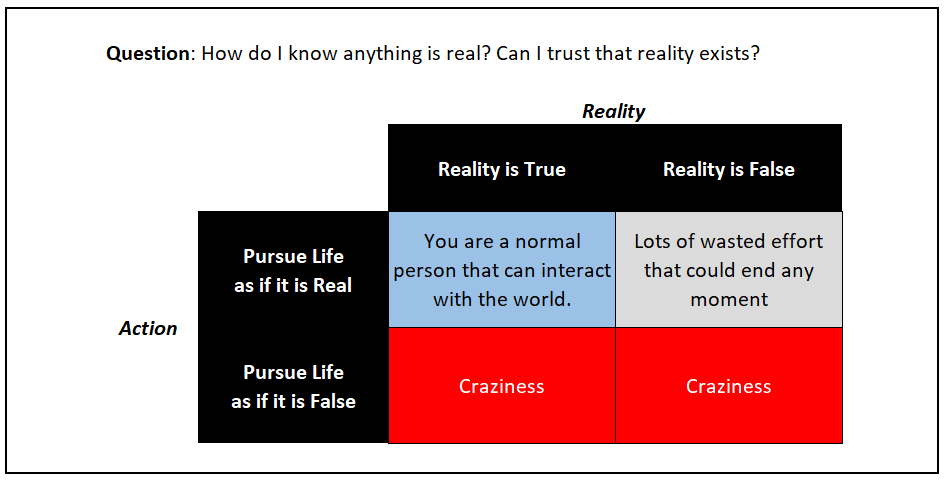

OK – what above the Cartesian question: how do I know if anything beyond my own thoughts is real?

Well, this one is a no-brainer (ha!). I concede, maybe craziness is an overstatement, but stick with me. Best to pursue life as if it was real, as if you weren’t a brain in a vat or a computer simulation. With all that red it’s so comical that you almost want to move on to the next example without stopping.

But wait a second… what if we had good evidence that reality is indeed false? Say the Simulation Argument is indefensible? Would we all swap our decisions to pursue craziness? No… we all pursue the top row alternatives because they are the right wager – regardless of the reality. It is necessary for living, and an expedient for making it livable.

The question is not what is real, but what you should chose to believe is real.

OK, check… the external mind problem is solved by necessary expediency, regardless of actuality. Another concept settled with the tool of Necessary Expediency.

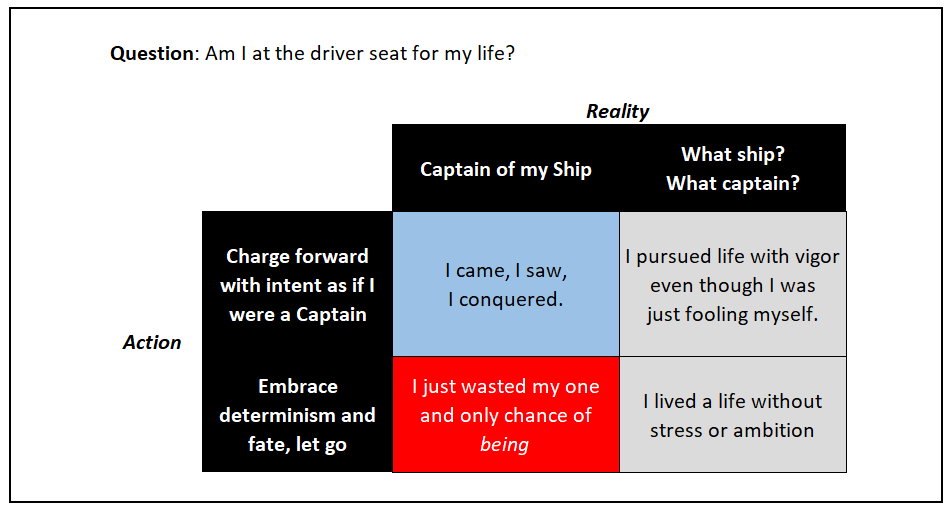

Next? Hmm.. it was just a few Modicums ago that I wrote “Having the self delusion of a driver’s seat is necessary for will and an expedient for action, both of which we can’t survive without.” There is another!

So this is pretty easy. Right now you can hear the intuition bell beginning to ring. So many questions of classic metaphysical philosophy have answers that seem to have a level of Necessary Expediency to them.

This is where the Grand Unified Theorem comes in. It is like Exupery’s Little Prince claiming “What is essential is invisible to the eye“. Here, it is “What is essential is a necessary expedience” – essential being defined as everything that matters (to me). Necessary Expediency underlies much of what I hold cognitively dear.

Preview: Deconstruction

But here is my final thought, to continue to riff on Exupery. I think it might equally be said that “Everything that is holding us back is a necessary expedience.” In particular, I believe that the subscription to the necessity of most beliefs has gone on so long and pervasively that we have forgotten that it is just an expedience, and not reality. I’m going to leave this thought, though, for part 2 for next week.

In the mean time, challenge yourself to look at the world and ask, am I believing in something because it is a necessary expedient for sanity or a fulfilling life, or because I really believe it?

2 Replies to “Pascal Was On To Something”